The Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef: The Föhr Reef

June 10 – September 16, 2012

Museum Kunst der Westküste, Alkersum, Föhr, Germany

In June 2012 the Föhr Satellite Reef was unveiled at the Museum Kunst der Westküste on the island of Föhr in the North Sea off the coast of Germany and Denmark.

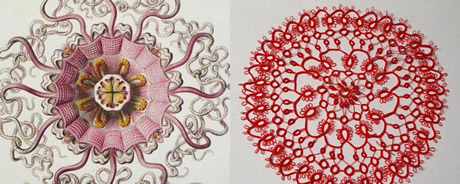

More than 700 people contributed corals to the Föhr Satellite Reef—pieces came in from all over Germany and Denmark and as far away as Holland, Luxembourg, Switzerland and Austria. More than 5000 corals were contributed, including some exquisite pieces of bobbin lace and tatting, traditional handicrafts for which the region is famous.

Displayed against the background of a stunning red sea, the Föhr Satellite Reef marks the apotheosis of the “rainbow style” of Crochet Reef curation.

The seeds of the Föhr Reef were planted in 2010 when museum director Thorsten Sadowsky saw an article in Die Zeit about the reef project.

The MKDW was then a new institution, recently opened, with a mission to focus on the seas and coasts of northern European nations. In addition to housing a collection of paintings depicting “the grandeur of the sea and the varieties of life along the North Sea coast” the Museum aimed to be hub for contemporary art. Sadowsky interpreted his mission broadly, with a central concern of his curatorial approach being cross-border dialogue, for Föhr resides at the boundary of modern-day Germany and Denmark, and has been claimed at times by both nations. Among its 9000 residents are native German, Danish and Friesian speakers. Sadowsky envisioned that a Föhr satellite reef would reach across national, cultural and social divides. The Crochet Reef‘s message about the urgency of ocean ecology and the need for community engagement spoke directly to the Museum’s concerns.

Föhr Reef workshops kicked off in January 2012 when the Museum hosted Margaret on a visit to the island. More than 200 people participated on the first weekend with a ferry-load of participants traveling from the Danish mainland. Many were expert handicrafters who’d already begun to crochet innovative corals, adding local flavor to the crochet tree of life.

Over the coming months the Museum held weekly workshops where island women island gathered, with tea and cakes served by Angela Skora-Weckenmann and the staff of Gretjens Gasthof cafe. Reef gatherings quickly became a focus of community building with “landfrauen” and “city women” from the towns of Wyk and Alkersum bonding over their hooks. In Germany’s formal culture, people who have known one another for decades often still call each other by surnames; at the Föhr Reef gatherings christian names soon became the norm, overcoming centuries of social separation. “The project became a beautiful embodiment of border crossing across many social lines” says Sadowsky. “It’s a been a very important way for bringing the people of the island together.”

The project also played a powerful regenerative role in the life of the Museum. Tragically in early 2012, the MKDW was damaged by a fire and its major galleries closed, including those in which the Föhr Satellite Reef and the IFF’s Traveling Exhibition were to be shown. Growing the Föhr Reef has been a “beautiful kind of healing” process for the Museum as it recovered from the fire, says organizer Lea Heim.

Lea had been handling incoming packages of coral and keeping track of the names of the Föhr Reefers. Some packages have arrived with no more address than “Föhr Reef, Alkersum, Germany.” Local women have also been recipients of enigmatically-labelled bundles and the island’s postmen soon got to know about the project and whom to entrust with the international tide of oddly-shaped mail.

With so much coral pouring in, curating and installing the Föhr Reef was a major undertaking. Gabriella Von Hollen-Heindorf spearheaded a nearly month-long effort, along with fifteen other core Föhr Reefers, and a huge substructure was built by the museum’s master carpenter. The entire structure breaks up into sections for transport, and after its showing at MKDW, the reef was exhibited at the Tøndern Museum in Denmark.

As the curatorial team honed their room-sized sculpture, they realized the importance of upward thrust and select contributors took on the task of making ever-taller spires. “It really became a challenge,” says Hollen-Heindorf, “who could make the tallest.”