A nexus of art, science, mathematics, environmentalism, and community practice.

Making is a science and coding is an art. In the Crochet Coral Reef project, art and science entwine in unexpected ways to explore how codes and materials can be manipulated to make a diverse taxonomy of forms.

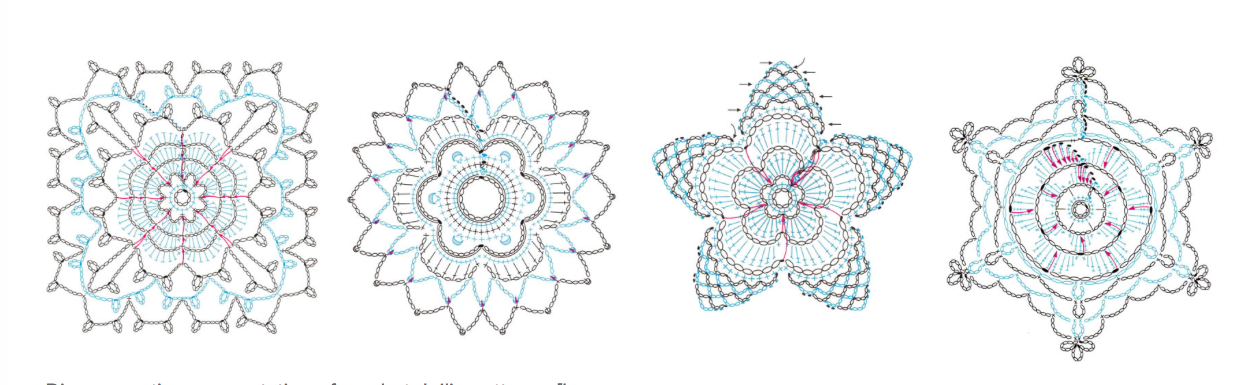

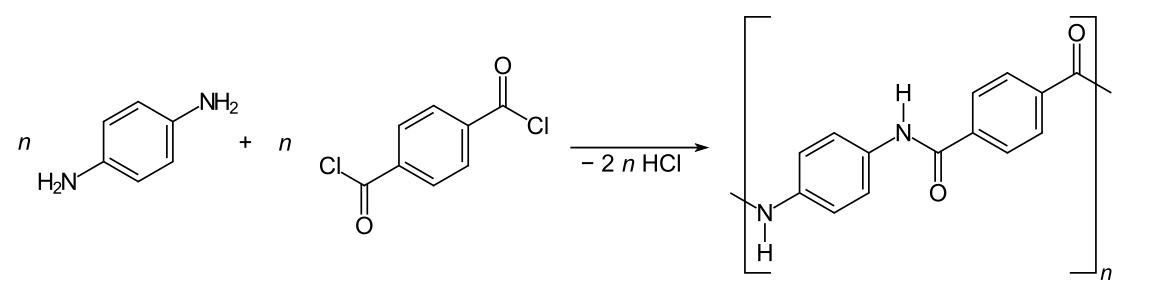

Where living organisms create themselves through code – the DNA residing in their cells – so the Crochet Coral Reef is underpinned by a code, the pattern of stitches that describes each individual piece. Crochet stitch patterns are actually a double code, for they be represented both by symbols (‘sc’ for ‘single crochet’, ‘dc’ for ‘double crochet’, and so on), and by diagrams. Here there is a parallel with chemistry, where molecules can also be described by strings of letters and a visual graphology. In both cases, symbolism is mirrored by a powerful visual analog.

Codes are only part of the ontology of things. In nature we see the same structures appearing in widely different branches of the Darwinian “tree of life.” Corals, kelps, seaslugs and cacti share similar hyperbolic forms, yet corals and nudibranchs are animals, while kelps and cacti are plants. Items in the Crochet Coral Reef that share the same code (or stitch pattern), may appear quite different when crocheted in different materials – an identical form made from stiff acrylic or floppy silk will have very different properties. We see here that matter matters, and what we make our sculptures from determines their look and feel as much as the codes they embody.

Thus while the project functions through coding, material exploration is vital. New ‘species’ of crochet coral ‘organisms’ come into being as more diverse materials are incorporated: wool, cotton, silk, flax, soy yarn, plastic shopping bags turned into “plarn”, electrical cables, videotape, and military-grade electroluminescent wire, have all been used. As in the evolution of life on Earth, so the Crochet Coral Reef becomes an ever-more diverse taxonomy.

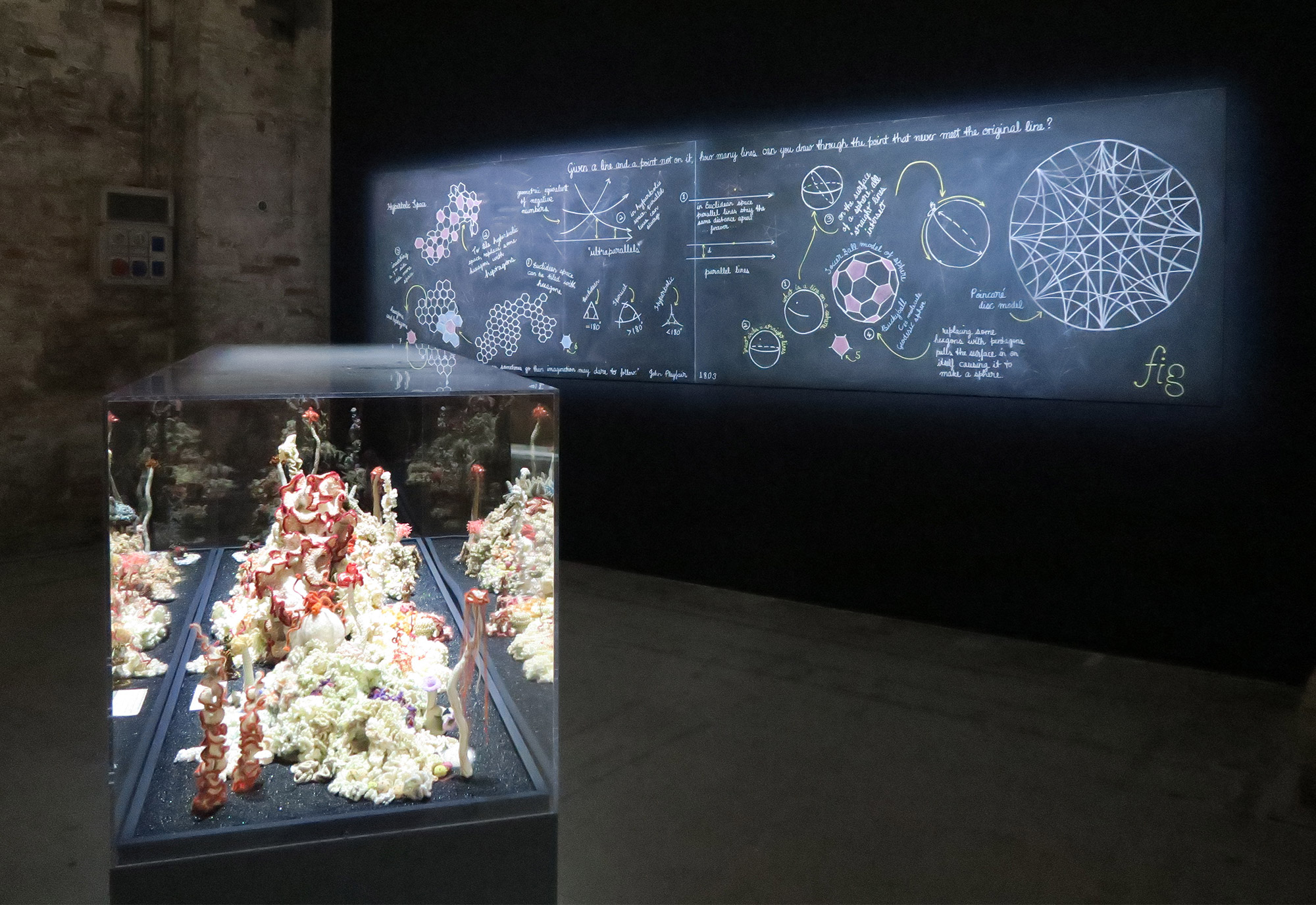

The Reef project is thus an artificial ecology emerging from an exploration of matter, form, and code. Here we witness the unfolding of a craft-based “chemistry” grounded in a language of the hands. Our aim is to produce lively looking sea-scapes, invocations of reefs that make no claim to being documentaries, yet which act on a psychological level to elicit in viewers a feeling of being “down there” under the sea.

More than play is at stake here. The project was inspired by the decimation of the Great Barrier Reef in Queensland, Australia, where the Wertheim sisters grew up. In 2005, after reading about coral bleaching caused by rising sea temperatures, Christine suggested crocheting a reef as a crafty response. Far from being an arbitrary choice, crochet was the logical medium, for the crenellated surfaces that living reefs generate are biological manifestations of hyperbolic geometry – a structure we humans can most easily model with crochet.

From this intersection of codes, craft, climate change and non-Euclidean mathematics, the Wertheims embarked on a journey of exploration uncannily paralleling the evolution of Earthly life. Time and contingency both play a role in the project, much as they do in the unfolding of living ecologies where chance and circumstance are central drivers of innovation. And citizen engagement is also key as communities around the world take up the challenge to create locally unique Satellite Reefs.

Science influences art influences science:

Where the Crochet Coral Reef was inspired by the mathematics of hyperbolic geometry and by the manifestation of such forms in living reefs, in 2020 the flux of ideas turned in the opposite direction when mathematician Shankar Venkatarami published several research papers about the underlying physics driving the formation of “negative curvature” surfaces in nature. This scientific work was inspired in part by the Wertheims writing about the Reef project. View pdf.