We Are All Corals Now

As the largest living system on our planet, the Great Barrier Reef is also the first living thing seen from outer space. Covering 133,000 square miles, this aquatic wonder is made up of over 600,000 separate reefs and sub reefs. Almost unthinkable then that such a vast entity could be threatened by human activity, and it is a mark of our power that its fate now lies in our hands.

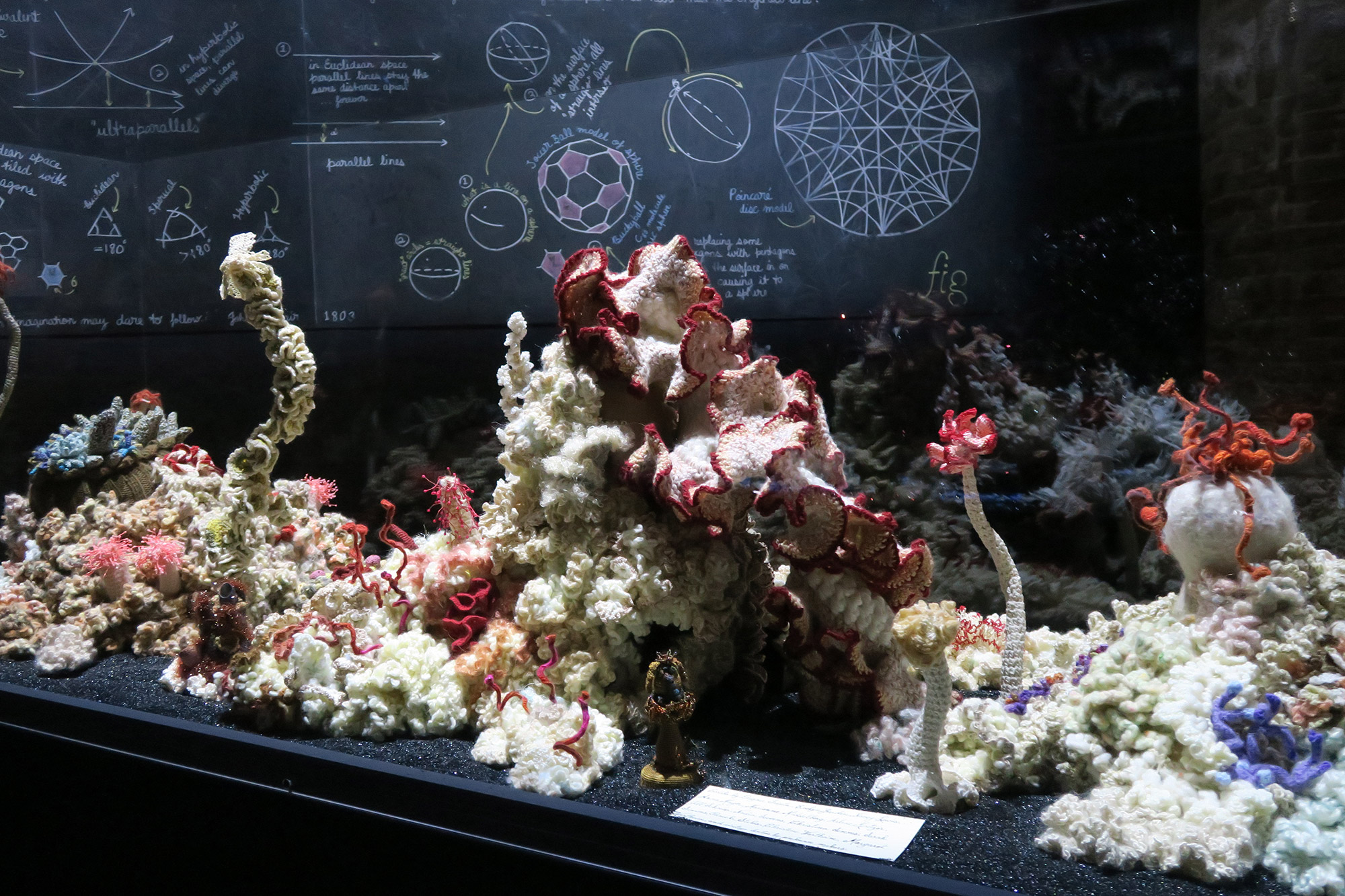

On the night in 2005 when the Wertheims began the Crochet Reef project, Christine joked that if the Great One ever died out our handicraft reefs would be something to remember it by. In little more than a decade this hitherto unthinkable notion has become a reality. A 2020 report in the Proceedings of the Royal Society revealed that over the past two decades fully half the corals on the GBR disappeared. If emissions continue at present rates this vast eco-marvel could be gone by the end of the century. Bleaching events, once rare spasms of coral whitening now occur every couple of years leaving corals too little time to recover – in both 2016 and 2017 record-breaking temperatures triggered mass bleaching events. As a homage to this tragedy, our archipelago of crochet reefs includes a Bleached Reef, an elegiac emulation of coral reef stress.

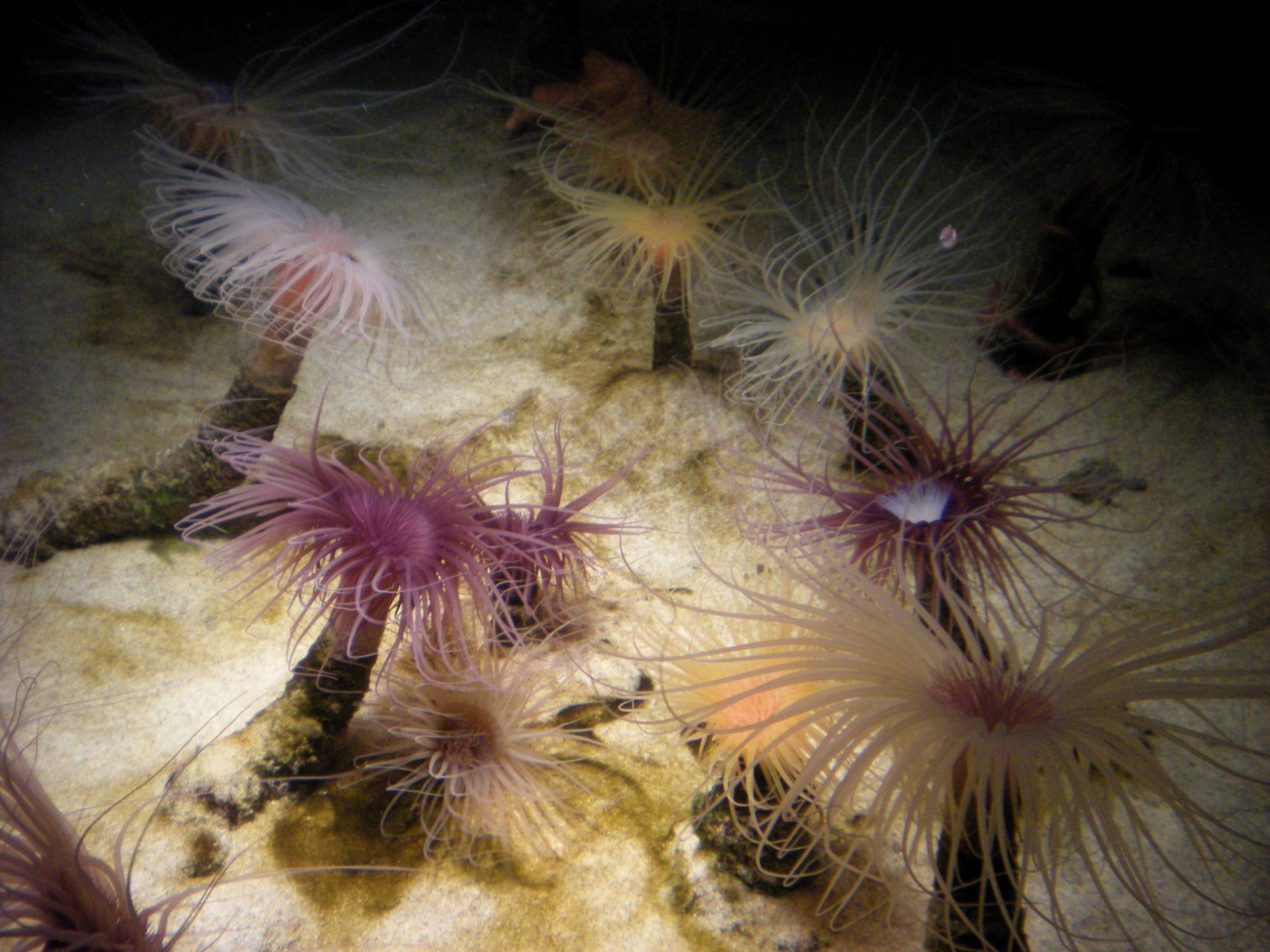

Though potentially vast in scope, living reefs are made by minuscule organisms – coral polyps just a few millimeters long. Individually, a coral polyp resembles a tiny jellyfish, and both organisms belong to the order cnidaria, an ancient and still mysterious branch on the tree of life. On their own, polyps are small and helpless, floating haplessly where currents take them, yet collectively, thousands of polyps can build a head of coral while millions of coral heads form the Great Barrier Reef. This natural collaborative artwork, authored by billions of minuscule critters, inspires the communal ethos of the Crochet Reef project.

In the face of climate change with its exponentiating cataclysms, we cannot wait for technological salvation. Though technology is a path we must surely also explore, all of us are called on now to do our bit. Just as coral polyps can achieve little on their own, but massive spectacles when they work together, so we humans are capable of extraordinary feats when we unite our energies collectively. We are all corals now.